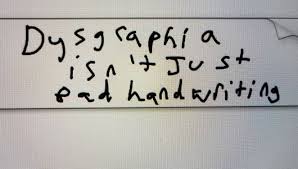

Dysgraphia affects a student’s ability to write coherently, regardless of their ability to read. Types identified include:

- Type 1: dyslexia dysgraphia where written work that is created spontaneously is illegible, copied work is good and spelling is poor. A student with dyslexia dysgraphia does not necessarily have dyslexia.

- Type 2: motor dysgraphia where the condition may be caused by poor fine-motor skills, poor dexterity and/or poor muscle tone. Generally written work is poor to illegible, even if it is copied from another source. While letter formation may be legible in very short samples of writing, this is usually after extreme efforts and the dedication of unreasonable amounts of time on the student’s part. Spelling skills are not impaired.

- Type 3: spatial dysgraphia where the condition is caused by a defect in spatial awareness and students may have illegible spontaneously written work as well as illegible copied work. Spelling skills are generally not impaired.

In general, written work may be presented with a mixture of upper/lower case letters, irregular letter sizes and shapes, and unfinished letters. Students struggle to use writing as a communication tool, and as so much effort goes into the actual writing process there may seem to be little imagination or thought in their work. They may have unusual writing grips, odd wrist, body and paper positions, and may suffer discomfort while writing. Excessive erasing may be evidenced as may a misuse of lines and margins. Students may also poorly organise writing on a page. Other difficulties may be observed in a poor organisation of ideas, poor sentence and/or paragraph structure and a limited expression of ideas. They may be reluctant to complete writing tasks or refuse to do so.

Strategies for Learning and Teaching

- Provide support with additional recording mechanisms where appropriate (e.g. charts, diagrams, dictaphones, models, voice recognition software and word processors).

- Minimise the amount of writing a student is required to do.

- Encourage oral responses.

- Use paper with lines that are raised; this will act as a sensory guide to help the student to stay within the lines.

- Try different pens and pencils to find one that the student is most comfortable working with.

- Explore concepts such as mindmapping®, spider diagrams and concept maps as a means of exploring topics or demonstrating learning.

- Adapt written activities and worksheets (e.g. instead of expecting a student to write full sentence answers, either encourage the student to fill in the missing word or circle the correct response).

- Use workbooks where appropriate to reduce the need to copy material from books.

- When organising written work, particularly projects, create a list of keywords.

- Use assistive technologies, such as voice-activated software, if the mechanical aspects of writing remain a major hurdle.

- Experiment with a variety of writing utensils (e.g. thick/fine-tip marker, use of grips on pencils, etc).

- Break tasks into small steps and allow adequate time for completion.

- Select and highlight most important errors not all errors – focus on the nature of the errors (quality) rather than the number of errors (quantity).

- Give regular constructive praise and encouragement and maintain high expectations.

- Limit copying from the board.

- Acknowledge that extra time is needed by students in order to complete written tasks.

- Explicitly teach organizational skills, for example POWER for essay writing:

- PLANNING

- ORGANISING

- WRITING

- EDITING

- REVISING